Star formation with unprecedented fidelity

At the Center for Astrophysical Research (CRAL) of ENS Lyon, I investigate the earliest stages of star and planet formation through high-performance computational astrophysics. By carrying out high-resolution simulations that self-consistently model gravity, radiation transport, and magnetic fields, I study the physical processes governing the formation and evolution of protostars and circumstellar disks. My research specifically targets the critical inner region (sub-AU scales) to understand the initial conditions for star and planet formation, as well as the dynamics of the star-disk connection.

My research directly addresses several long-standing challenges in astrophysics, including the angular momentum problem, the magnetic flux problem, the luminosity problem, and the disk mass problem. My work also extends to planetology, in which I offer insights on the transport of high-temperature condensates in the early solar system, thus allowing us to better interpret the composition of meteorites. My simulations incorporate advanced numerical techniques and leverage high-performance computing to achieve unprecedented fidelity in modeling these complex and highly non-linear astrophysical processes.

Below is a curated gallery of my work:

The Method: Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR)

Simulating the birth of stars and disks presents a formidable numerical challenge, requiring a model that couples highly non-linear physics with an immense dynamical range. My simulations span over 17 orders of magnitude in density (\(10^{5}~-10^{22}\ \mathrm{cm^{-3}}\)) and 8 orders of magnitude in spatial extent (\(10^{4}~-10^{-4}\ \mathrm{AU}\)). To tackle this challenge, I employ Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR), which selectively increases the resolution in collapsing regions. The animation below illustrates this dynamical range: the color map shows the gas column density, while the white contours trace the AMR levels, highlighting how the simulation adapts to resolve relevant structures across different scales.

Birth of protostars and circumstellar disks

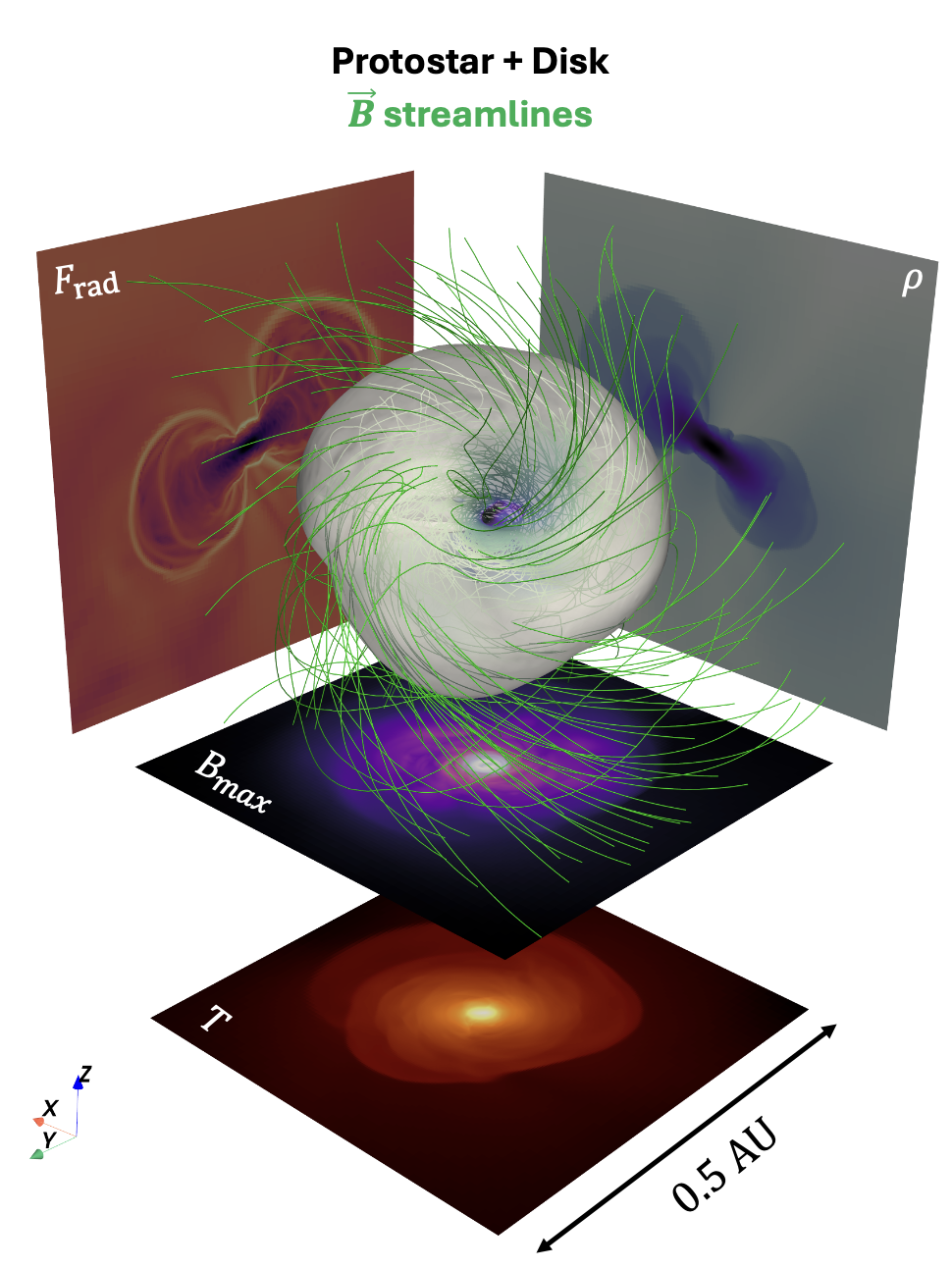

While disks are often studied in their evolved stages as planet-forming environments, my simulations tackle their initial formation via the gravitational collapse of a gas and dust cloud. By modeling the full dynamical range of the first and second collapse (Larson 1969), these simulations self-consistently form both the protostar and the circumstellar disk, providing a first-principles framework for their detailed study.

Brown Dwarf Formation

CNRS Press Release. Brown Dwarf are rather puzzling objects: too massive to be planets, yet not enough to fuse hydrogen and be considered stars. Their dominant formation mechanism remains debated, with proposed scenarios including turbulent fragmentation, disk fragmentation, and ejection from multiple systems. My simulations explore the gravitational collapse of low-mass dense cores to simulate the direct formation of Brown Dwarfs. Below, you can find a 3D animation showcasing the first month after the formation of a Brown Dwarf through gravitational collapse. Born with a radius of \(\approx 0.75\ \mathrm{R_{\odot}}\) and mass \(\approx 0.8\ \mathrm{M_{Jup}}\), it quickly grows by accreting from its surroundings. Angular momentum accretion also causes it to flatten along its equatorial regions.

Interpreting the meteoric record

Calcium aluminium-rich inclusions (CAIs) are high-temperature condensates that directly cristalyzed close to the young Sun shortly after its formation. Their presence in carbonaceous chondrites beyond the orbit of Jupiter suggests that they were subsequently transported outward to the colder regions of the protoplanetary disk where these meteorites formed. My simulations of the protosolar disk’s early evolution reveal a natural mechanism for this transport: the rapid initial expansion of the disk itself. The animation below illustrates this process, disk surface in blue and the protostellar surface in green. White streamlines are velocity vector field streamlines that illustrate polar accretion into the protostar, and the image panels are cross-sectional slices displaying the radiative flux. Notice how efficient the expansion is, with the disk growing to \(\approx 0.5\) AU in radius in less that 1.5 years.

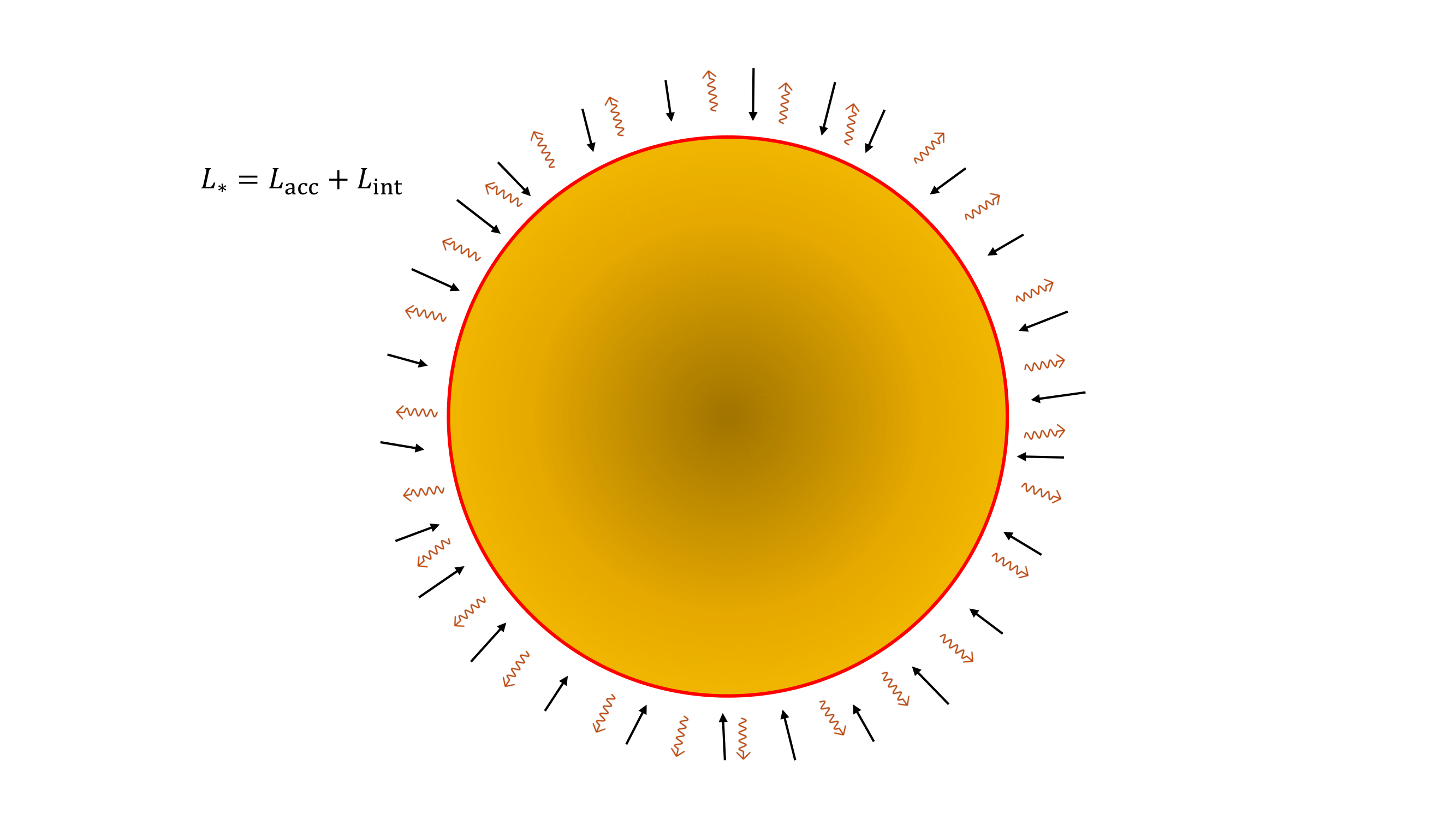

Analyzing the radiative efficiency of protostellar shock fronts

Protostars mainly shine by radiating away the incoming kinetic energy of the gas that they accrete as accretion luminosity \(L_{\mathrm{acc}}=\frac{GM_{*}\dot{M}}{R_{*}}\). Understanding how this energy is processed at the protostellar shock front is crucial for accurately modeling the protostar’s subsequent thermal evolution and for reliably quantifying its radiative feedback. By employing high-resolution simulations that fully resolve the radiative shock front, its radiative behavior can be studied in detail.